COOPER COLE is pleased to present Chrysanne, a solo exhibition by Chrysanne Stathacos. This exhibition is guest curated by Gia Liapi and marks the artists second solo exhibition with the gallery.

The following text written by Gia Liapi accompanies the exhibition:

Chrysanne Stathacos has been unsettling the linear structures of patriarchy since the moment she arrived in this world.

In her autobiographical text “Forgotten Wishes”, Chrysanne writes:

Birth.

I had been my grandfather’s forgotten wish that he loved very much. Papou had wished for the birth of a grandson, his namesake, a new Charlie, to continue the Greek male line.

I surprised him.

Perhaps she was born in the wrong era, or perhaps she arrived right on time:

Lala, my grandmother, responded to his behavior by finding a four-leaf clover, an omen of Delphic oracle proportions; I was a lucky girl baby, perfect, no matter what my sex.

One time while reading in Chrysanne’s guest room (in which she has graciously hosted me since my arrival in Toronto from Athens last January) I learn that her mother shared her labour ward with an artist who drew a pastel portrait of her as an infant. My gaze turns to the wall:

To this day a small pastel portrait of a tiny baby, framed in pink with a faded four-leaf clover tucked in the corner hangs in my bedroom.

I had been wondering what the picture was… when asked, Chrysanne replies:

“Sometimes you can’t escape.”

In the many conversations I have shared with Chrysanne and her family, stories have often circled around three recurring themes: how she always knew that she would be an artist; how much of an “artist’s attitude” she had always had; and how much her family had always been staunch supporters of her path.

Chrysanne’s early life seems to have imbued its psychic resonance across her transdisciplinary practice, which integrates affect and intuition as its key methodologies. As an emigrant from the United States to Canada, but raised with the customs and traditions of her Greek heritage, and its geographically inherent roots as a cultural crossroads, Chrysanne’s experience and identity is steeped in hybrid dialogues. She is committed to epistemologies that are grounded in social practice, ritual, and spirituality, drawing from across the spectrum of Buddhism, astrology, tarot, and Greek mythology, to address some of the unattended consequences of the social injustices that her over-five-decade career traces.

Chrysanne has generously and tirelessly employed all-embracing communal practices to create social infrastructures that sustain artists and foster kinship. Relationality, empathy, and a deep devotion to female empowerment form the core of her artistic and quotidian practices. Besides her early contributions to the broader arts community as both an artist and educator in Toronto and New York City. She is a devoted Buddhist, who works to reclaim the lost traditions of Tibetan women practitioners while supporting female monastic communities in Tibet and India.

Chrysanne often tells me:

I am a collagist.

This sentiment makes me think about collage as a broader composite approach. A coming together of various divergent, or otherwise orphaned parts to form a new whole. Her collage mode of living and working speaks to an expansive and planetary way of thinking and being that makes room for the multiplicities and imperfections of the life we experience in this world.

Chrysanne comprises a constellation of gestures that reflect this approach. A place of remediation, esoteric, yet plural. It traces back ancestral narratives to open a discourse on belonging that reaches beyond individuality to shine light on our collective future.

In this eponymous exhibition, the first solo presentation since the passing of her mother, we witness the non-chronological interplay of undisclosed works and recurring touchstones in Chrysanne’s practice. Ivy, roses, and women’s hair – all motifs loaded with mystic meaning – are paired with relics, artifacts, and garments, each a faithfully preserved personal treasure of great sentimental value. Together these sources and references weave a tight genealogy leading back to antiquity while mirroring both present and future. The pieces here contribute to the personal lineage of family archeology that has been a constant in her practice. Stories of Chrysanne’s upbringing by her immigrant grandparents, with their idealized vision of a distant homeland, are encapsulated in these works that explore a sense of corporeality and the meaning-making made possible by our intimacy with the objects and garments that surround us.

The impression of her late mother’s nightgown on canvas – a piece that’s hung prominently in Chrysanne’s living room since its creation – is a quiet mourning gesture that reconfigures the relationship between bodily agency and the rituals and archival practices that shape memory. A box of heirloom gloves, passed down through generations, gives rise to new resonances of time and its strange mix of clarity and obscurity. These works are part of a new series that incorporates an antique tarot deck once accidentally washed in the laundry by her mother. Intimacy, recollection, and the restorative formation of a fragmentary narrative, are all powerfully at play.

Through these works and more, Chrysanne narrates her loss in order to recuperate hope. The inclusion of archival relics is more than mere nostalgia to her. In his 1988 essay on Chrysanne’s paintings, G. Roger Denson writes:

“It is strategic that in Stathacos’ quest for meaning, rather than resorting to isolating, decontextualizing and exhibiting yet another found object—which would signify being, but not becoming or ceasing—Stathacos chose to print traces of objects left, as traces can only be left, by the objects themselves. By traces, I mean impressions left on a surface by an object after it has been inked or painted and then pressed wet against a surface with applied pressure.”

In the recent months I’ve spent living and working in her studio, I’ve often found myself wondering about both the traces and the impressions her paintings give to re-animate the objects she has recontextualized within them. The subjects she’s imprinted are neither in their initial form, nor in a new condition. They seem to contain marks of some core essence, as if the psyche (soul) of the object carries on. Her paintings are very active in their presence because they are, to use her own words, “performance paintings.”

Performance and painting are mediums that when placed together, fray temporal barriers, generating a kind of perpetual timeless present of being. To prevent the oblivion of unsung histories and epistemes, she often integrates organic elements with spiritual, feminist, and medical properties, such as herbs traditionally used to administer abortions. Those elements are surrendered to a process of subordination, sacrificing their initial form in a quest for meaning gesturing towards healing that stretches across time.

Chrysanne’s complex techniques and sources treat fragility in a manner that creates a new kind of soft monumentality. At the center of this exhibition we find a fluffy white flokati rug purchased by her mother in the 1960s. Dating back to ancient times, thick woolen flokati have been an important part of rural Greek tradition that continues to serve as a hallmark for communal gathering. By sharing specific cultural signifiers like this, Chrysanne works to expand our collective memory of gatherings deconstructing the notions of time and identity that are entwined within memories and artifacts. On the flokati we can watch the video work “grandfather dream” (2007), where Chrysanne’s father, Dean, plays Greek diasporic folk songs on the piano. Chrysanne combines this document with her pappou’s (grandfather’s) footage of travels to Greece in the 1950s, creating a moving portrait of her family’s immigrant trajectory while reframing the symbolic elements of a lost and longed-for homeland. These perpetual spirals of shared signification contain themes of belonging and touch on the complicated feelings of inheritance many share across diverse cultures. Her father’s music provides a soundscape for the whole exhibition, tracing tales of exodus and distance that inevitably lead to Chrysanne’s work, binding it into a one psychic space through melody.

With many decades of artistic practice in her own committed signature behind her, Chrysanne can be considered among the pioneers of ecofeminism. For the “Petal Series” she reverses her own technique, and instead of crushing roses, prints directly on their individual plucked petals. The imagery consists mostly of women in resting poses, pulled from nineteenth century erotica. Together with the “Rose Ladies” she made in 1996, which are presented now for the first time, she knowingly employs the rose’s resonance with femininities that traces back through mythologies associated with the goddess Venus. In doing so she revives these links, critiquing how female sexuality and the autoerotic have inherently been obscured and fetishized.

In the early 1990s Chrysanne channeled her feminist frustrations and ambitions into the creation of Anne de Cybelle. Placing herself within the genealogy of women artists taking on another name and persona as an act of defiance and self-protection, as females often rendered vulnerable when using their own voices to confront injustice. In her 1997 video that followed the “Rose Petal” series, Anne de Cybelle, introduces a future world that’s radically transformed, inviting us to encounter a reality that’s flipped on its head from the world’s current state. Among the many references that reflect our present, she subversively refers to the “Rose Petals” as a futuristic technology of meditative practice. In the tradition of witchcraft and many sacred occult practices, the specific technology Chrysanne used to create this series remains a firm secret.

In Chrysanne’s “Forgotten Wishes” text, the chapter titled “Birth” ends with:

Papou arrived, took one glance at this lucky beautiful infant, bald

pink head, rounded cheeks, and fell madly in love. Now he was to be the only one to hold me. I had seduced my Papou by holding onto his finger and looking at him in the eyes.

Chrysanne Stathacos (b. 1951) is a multidisciplinary artist of Greek, American and Canadian origin. Her work has encompassed printmaking, textile, painting, installation and conceptual art. Stathacos is heavily involved with and influenced by feminism, Greek Mythology, eastern spirituality and Tibetan Buddhism, all of which inform her current artistic practice. She has participated in countless international exhibitions in various media, but she is most known for her unique combination of performance and installation. Stathacos’ recent solo exhibitions include Cooking with Roses, The Buffalo Institute of Art (2022), Pythia,The Breeder, Athens (2017) and Gold Rush, Cooper Cole, Toronto, (2018), and Do I Still Yearn for My Virginity?, Situations, New York (2018). Stathacos presented The Three Dakini Mirrors (of the body-speech and mind) in the 13th Gwangju Biennial Minds Rising Spirits Tuning curated by Defne Ayas and Natasha Ginwala (2021); she also presented Five Mirrors of the World (2019) at The Sculpture Park, Madhavendra Palace, Nahargarh Fort, Jaipur. Recent exhibitions include Every Moment Counts: AIDS and its Feelings at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Norway, curated by Ana María Bresciani and Tommaso Speretta (2022). Her Rose Mirror Mandala series was originally created to be presented to the Dalai Lama in 2006 for his visit at the University of Buffalo, and was later included by AA Bronson in many exhibitions including The Temptation of AA Bronson, Kunstinstituut Melly (Formerly known as Witte de With) for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam (2013). She is a founding Director of Dongyu Gatsal Ling Initiatives, a non-profit organization that works to help Tibetan Buddhist women practitioners in the Himalayas, inspired by the life work of Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo. She is represented by The Breeder, Athens. Stathacos’ works are included in public and private collections including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria; the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. The Chrysanne Stathacos fonds is located in the Archives and Library, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Stathacos currently lives and works between Athens, Greece and Toronto, Canada.

Gia Liapi (b. 1988) is an independent contemporary art curator and researcher. She has been involved with both public and private institutions internationally, including 2023 Eleusis, European Capital of Culture (GR), The Contemporary Art Gallery Vancouver, BC (CA), DESTE Foundation (GR), and Schwarz Foundation (DE) among others. She has curated exhibitions across institutions, commercial galleries, artist-run centres, and social projects such as, the B&M Theocharakis Foundation and the Fine Arts & Music, AKSS Foundation, AMA House, Callirrhoë Athens, Greek Street Paper “shedia Home”, MISC Athens, P.E.T. Projects, and Zoumboulakis Galleries. Recent curatorial awards include Canada Council for the Arts (Explore and Create, 2023), and NEON Foundation (GR) as Emerging Curator (2020). She was a runner-up for the NEON Curatorial Award 2020 in collaboration with Whitechapel Gallery in London (UK) and a Curatorial Resident of Schwarz Foundation (ASP, Samos, 2019). In 2023 she was the co-curator of the large-scale exhibition “This Current Between Us”, at the Historic Steam Electric Power Station of Greece with the support of the Greek Ministry of Culture. Between 2019 to 2023 she was the Exhibitions Director and Curator for Zoumboulakis Galleries, Contemporary (Est. 1966). She has contributed texts in catalogues and journals in Greece and abroad. She is currently a Teaching Assistant at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, University of Toronto, and a graduate student in Curatorial Studies, supported by a University of Toronto Fellowship, and the John and Myrna Daniels Foundation. She lives between Athens (GR), and the lands of Treaty 13 known as Toronto, ON (CA), and works internationally.

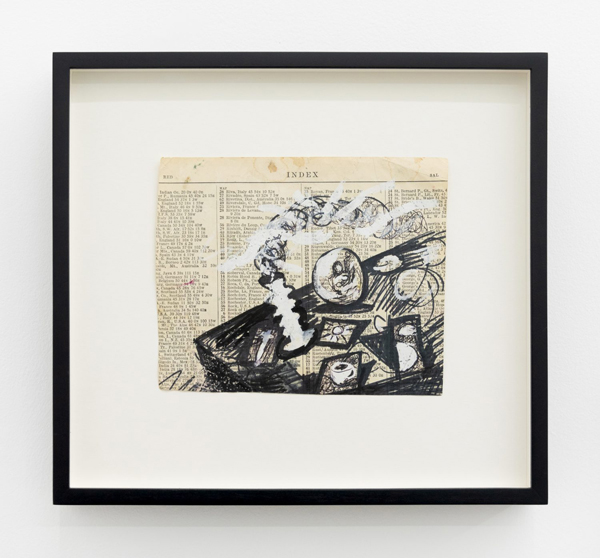

Pen and ink on rag paper 9.75" X 11" 24.76cm X 27.94cm

Pen and ink on rag paper 9.75" X 11" 24.76cm X 27.94cm